By Michael Cañares

The author is Regional Research Manager at the Open Data Lab Jakarta This article was first posted Sept. 28 on the Web Foundation blog. The first paragraph is the Web Foundation introduction.

Can open data improve people’s access to information? Michael Cañares, Regional Research Manager at the Open Data Lab Jakarta looks at how citizens in Banda Aceh used Indonesia’s Freedom of Information Act, and how open data worked to bolster citizen participation. If you’re heading to IODC, join him at the Open Data Research Symposium and at our session “From Open Data Research to Policy” on Friday from 11:00 to 12:00 in Room E.

Two years ago, I remember presenting what open data can do for the Philippines at the Good Governance Summit in Manila. At the time, Freedom of Information (FOI) advocates told us that the open data movement was highjacking the freedom of information agenda by giving governments a new outlet for transparency, relegating FOI requests to the bottom of the priority list. They raised concerns that governments might just focus on releasing large amounts of data the average person could not understand or use instead of responding to citizens’ questions.

While FOI and open data differ in their approach, their aim is aligned: provide citizens with access to government information to improve transparency and public service delivery. But our research has shown that FOI and open data efforts can actually complement one another. At Open Data Lab Jakarta, we argue that open data can make FOI more powerful, especially when the response to a request for information includes a disclosure of data.

In Indonesia, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) of 2008 provides the legal guarantee to access information held by public bodies through proper request channels. As part of the FOIA, the city government of Banda Aceh established thePejabat Pengelola Informasi dan Dokumentasi (PPID) platform to manage citizen access to information.

At the Open Data Lab Jakarta, we’ve been working with the city of Banda Aceh. Although the district is leading the country in its FOI implementation, the number of requests submitted by citizens is still very low – at only 40 requests in 2014. Of these the government responded to 34 requests, providing citizens with information such as school profile, teacher profile, population data, and results from the general election. But if the government was responding to these requests with useful information, why weren’t more people and organisations taking advantage of it? We asked a number of local civil society and community organisations to find out how we could increase public access to information and also learn about the priority needs of citizens in the education sector.

Two glaring obstacles were found: 1. The complex process for making an FOI request, and 2. Citizens’ limited belief in the government’s capacity to respond. Therefore, judging by the diagram in the picture above illustrating the lengthy FOI request process, many citizens decide, even when the information is offered at no fee, the cost in time of requesting information is not worthwhile given they might not get the information they really need.

We wanted to test whether we could increase demand for government information by supporting the government in opening a central portal online with information that citizens want. We piloted this idea through a portal containing key priority datasetsheld by Banda Aceh’s education department. We then worked with local civil society and community organisations to help them learn how to understand, analyse and translate government data into actionable information.

To make sure the online data would be used, we went back to the civil society groups we consulted about the FOI process and held a series of workshops. Our goal was to enable them to act as data and information intermediaries between the government and citizens, producing actionable insights.

One year after this initiative started, we began to see results. While the FOIA requests continued to stagnate, we saw an upsurge in open data downloads.

Why did this happen? Eva Khoviva, a CSO worker at PKBI, one of the CSOs that we engaged with using health data, said:

“The ease of accessing government data through the portal is one important factor. We do not have to go physically to the offices anymore and file a paper request or request for data online and wait for a reply. We do not have to go through different sets of processes. If we want to analyse data on morbidity, for example, which is one our concerns as an NGO, we just download the data from the portal and do our analysis.”.

But for Askal, chief of anti-corruption group Gerak Aceh, it is not just about the availability of data, but also of the capacity of people – more particularly civil society organisations – to be aware that the data exists, to access and analyse it, and to produce something useful out of the datasets.

“If people do not have the capacity, they will not be interested with any open data portal”, he added.

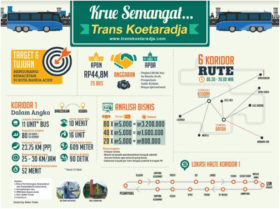

A year and a half year later, civil society organisations are working with tech communities to produce important products using data proactively disclosed by the government. The education data pilot extended to other sectors as health and transportation. Below is an example of an offline poster displaying information on Aceh’s mass transport system which is also available online. Without open data, this poster will be difficult, if not impossible to produce.

FOI is one of the cornerstones of government transparency efforts, and more must be done to ensure FOI requests processes are streamlined to ensure citizens receive timely responses and are encouraged to submit more requests. It is also critical that citizens are able to submit requests to question government data provided on portals, and receive complementary documents and information.

For its part, open data can complement the reactive nature of FOI requests with proactive data disclosure. The data disclosed also allow citizen to use analytics to visualise important information in an easily digestible way for citizens. The city government of Banda Aceh has recognised this and they are currently finalising a city regulation on data management systems with strong open data and proactive disclosure provisions.

If you’re heading to the International Open Data Conference 2016 in Madrid, Spain, come hear more about out work at the Open Data Research Symposium and at our IODC session “From Open Data Research to Policy” on Friday from 11:00 to 12:00 in Room E. You can see how data affects everyday life in Indonesia at the Web Foundation’s Open Data Lab Jakarta, “Data2Life. Life2Data.” photo exhibition in the IFEMA lobby.

Follow us on Twitter @ODLabJkt and @mikorulez for more updates!

Filed under: Latest Features