By Vincent Mabillard

The author is a Research Assistant at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration, University of Lausanne Lausanne, Switzerland. This is an excerpt from a longer paper (pdf) that also provides an overview on the adoption of FOI laws, discusses their different characteristics and suggests possible ways to address FOI in a comparative perspective. This excerpt compares the levels of FOI requests in 11 jurisdictions and where they come from. The full paper goes into greater length in “case studies” about each of 11 subject jurisdictions: Germany, Ireland, Mexico, Scotland, Switzerland, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and the United States.

The evolution of requests submitted to public authorities

The volume of requests received by national administrations form a relevant aspect of FOI because they give an indication of the laws’ efficiency.

Of course, other indicators should be taken into account in any quantitative study on access to information, but the usage of the law provides an interesting dimension. In this section, requests from 11 jurisdictions will be compared and a general comment on the evolution of requests submitted to public bodies will be provided.

The origin of the requests is of crucial importance because they give an idea of the usage of the law, of the requests’ purpose, of the involvement of the general public and, in some cases, of the political use of this right. Unfortunately, many states do not maintain a record of all complaints received and processed, and most often do not present any information about the requesters. It is the case in New Zealand (see Annual Report 2014/2015 of the New Zealand Ombudsman Office) and Canada in recent years.

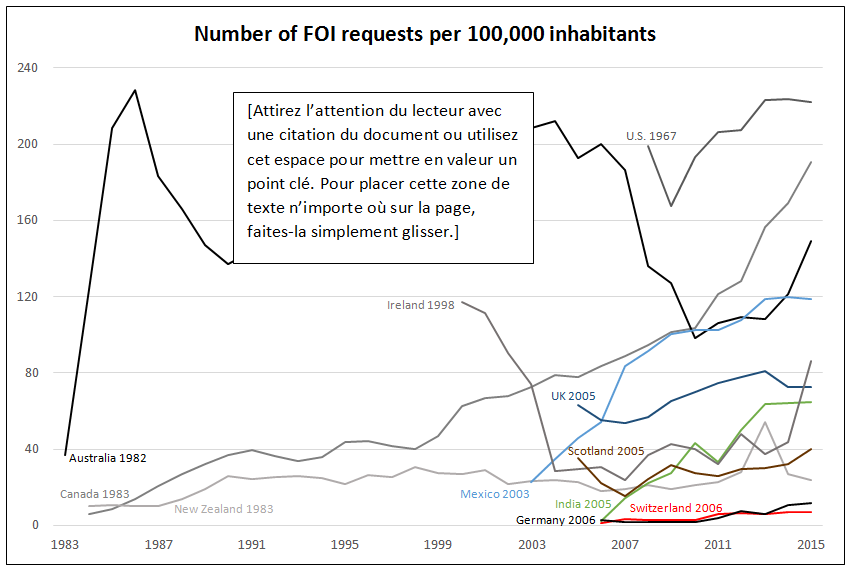

Graph 2 below shows the evolution of FOI requests submitted to national authorities since the enactment of the law in all selected jurisdictions.

The more or less recent history of FOI in a given country certainly play a role as mentioned by Holsen and Pasquier (2011). The graph should be analyzed cautiously, since data vary according to the type of requests considered. Details about the exact count will be provided hereafter in sections dedicated to each state.

Data from the United States dramatically change after 2007 (the different count will be explained below). As a result, in spite of the early adoption of the FOIA in the U.S. (it came into force in 1967), only figures published after 2007 will be presented in the graph. There are similar problems with Ireland. Countries with available data (at least for the author) have been selected for this comparative study. Annual reports, academic articles and contacts with the Ombudsmen offices and other national authorities in charge have enabled us to gather all these data, following a first effort from Pasquier (2011).

All jurisdictions have in general experienced an increase in the volume of requests submitted to the national authorities.

One can also notice that the total number of requests is higher in countries that have adopted a FOIA quite early, as it is the case in Australia, Canada, and the United States. New Zealand is an exception here, but once again the graph should be considered cautiously. Figures for New Zealand refer only to complaints received during the year under the Official Information Act, a distinction that is not always done in other countries because of a totally different system, a different type of counting or a lack of resources to publish more detailed reports. In New Zealand, access to information is ruled by several laws (Ombudsmen Act, Official Information Act, Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act, etc.). If all matters would have been taken into account, the graph would look completely different: indeed, the total amount of complaints (under all existing acts), other contacts and monitoring activities peaks at 12,151 in 2014/2015 (see Annual Report 2014/2015 of the New Zealand Ombudsman Office). There are also partial data in some cases. For instance, figures for FOI activity have not been supplied by the Irish Defense Forces in 2002. Details about all jurisdictions will be presented in separate sections later.

In spite of the general trend towards more requests since the implementation of FOI laws in the 11 jurisdictions included in our study, one can also notice that the evolution is not linear.

For instance, Australia has witnessed a massive increase of complaints in the early 1980s, followed by a sharp decrease in the late 1980s, and then again in the late 2000s. Reasons for this evolution has not been fully explained so far. More recent experiences show contrasted results. While FOIA remain not very popular in Switzerland and Germany, the opposite is observed in Mexico and India, where the volume of requests is now substantial – 150,595 in Mexico and 845,032 in India in 2015. After a successful first year, Scotland has experienced a decrease of complaints until 2015, when an unprecedented total amount of 2,155 was reached. Finally, complaints have also risen in the United Kingdom, though not in a linear fashion, and have remained more or less stable over the past two years. Graph 2 presents a comparative perspective on requests submitted under FOI laws (per 100,000 inhabitants).

Graph 2. Evolution of FOI requests (1982-2015)

The increase of requests can be analyzed through absolute numbers, taking into account the year in which the Act came into force and the last data available (2015). However, figures for the U.S. are not based on requests received in 1967; 2008 becomes the reference year here due to a change in the counting method which affects considerably the total amount of complaints. Furthermore, statistical periods are not determined in the same way in all jurisdictions, but as follows:

– In Germany, Ireland, Mexico, Scotland, Switzerland, and the UK, the reference period is the calendar (Gregorian) year (1st January – 31st December);

– In Australia and New Zealand, the financial year is preferred (1st July – 30th June);

– In Canada and India, the fiscal year starts from 1st April and ends on 31st March;

– In the United States, the fiscal year begins on 1st October and ends on 30th September.

For this reason, data in Australia and Switzerland are based on 6 months only in the first FOI “annual” report. Indeed, 95 requests were submitted in Switzerland between June and December 2006; in Australia, the law entered into force in December 1982, and the statistical period ended on 30th June 1983. If the difference is not remarkable in the Swiss case, there is a significant gap in Australia, with 19,227 complaints received by the governmental agencies the following year.

As shown in table 1, the increase of requests has been impressive over the last 50 years in Canada. The trend seems to continue and even to accelerate in the 2010s. Switzerland and Germany have also experienced a significant increase, but figures remain quite low because of a slow start (247 requests submitted in Switzerland in 2007 and 2,278 in Germany in 2006).

On the contrary, Irish and British authorities have received a high number of complaints during the year following the enforcement of the law, although data are missing for Ireland in the first two years (1998-1999). They have since remained rather stable, with a slight increase in the UK and decrease in Ireland. The situation in Mexico is completely different. The volume of requests has strongly increased in this country. This is even more the case in India, where 24,436 complaints had been filed in 2006 and almost 850,000 in 2015.

Table 1. Absolute number of requests made in 11 jurisdictions (comparison from the year following enforcement of the law to 2015)

| Year following the enforcement of the law | 2015 | |

| United States (1967) * | 605,491 | 713,168 |

| Australia (1982) | 5,669 | 35,550 |

| Canada (1983) | 1,513 | 68,193 |

| New Zealand (1983) | 318 | 1,090 |

| Ireland (1998) ** | 4,448 | 3,958 |

| Mexico (2003) | 24,097 | 150,595 |

| India (2005) | 24,436 | 845,032 |

| United Kingdom (2005) | 38,108 | 47,386 |

| Scotland (2005) | 1,800 | 2,155 |

| Germany (2006) | 2,278 | 9,376 |

| Switzerland (2006) | 95 | 597 |

* 2008 (for statistical reasons mentioned above)

** 2000 (for statistical reasons mentioned above)

Of course, the population size also matters, as shown by the figures presented in table 2 (number of requests per 1,000 inhabitants).

Here, we can see that the number of complaints remains very low in Germany and even more in Switzerland. Although there has been an increase in the first decade (2006-2015), both states score poorly compared to most countries that have adopted FOI laws in the early 1980s, and populous countries that have adopted a FOIA more recently, like India and Mexico. Once again, data for the UK is more or less stable (up from 0.73 requests per 1,000 inhabitants in 2005 to 0.83 in 2015). Population statistics have been retrieved from the World Bank database (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL), except for Scotland, where data have been collected on the National Records of Scotland website (http://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/stats-at-a-glance/registrar-generals-annual-review/archive).

Table 2. Number of requests made in 11 jurisdictions, per 1,000 inhabitants (comparison from the year following enforcement of the law to 2015)

| Year following the enforcement of the law | 2015 | |

| United States (1967) * | 1.99 | 2.22 |

| Australia (1982) | 0.37 | 1.49 |

| Canada (1983) | 0.06 | 1.90 |

| New Zealand (1983) | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| Ireland (1998) ** | 1.17 | 0.85 |

| Mexico (2003) | 0.23 | 1.19 |

| India (2005) | 0.02 | 0.64 |

| United Kingdom (2005) | 0.63 | 0.73 |

| Scotland (2005) | 0.35 | 0.40 |

| Germany (2006) | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Switzerland (2006) | 0.01 | 0.07 |

* 2008 (for statistical reasons mentioned above)

** 2000 (for statistical reasons mentioned above)

Several factors may help to explain these differences.

Apart from the recent character of the law, institutional variables play a significant role, as explained by Mabillard & Pasquier (2015). For instance, federal systems with FOI laws at subnational levels may have a diminishing effect on the volume of requests submitted at the national level.

At the same time, direct democracy instruments, such as popular initiatives and referenda in Switzerland or in regions/states/provinces in other countries may also have an effect on citizens’ needs to get access to information detained by public authorities. Furthermore, the diverse systems of FOI partly explain the different figures presented in table 2: not only the legal basis differs, but the counting is affected.

Consequently, it remains difficult to carry out a comparative research on the volume of complaints received by governmental bodies in all the jurisdictions considered here because of their own characteristics. However, it is possible to highlight some common features of FOI laws and, in a comparative perspective, to see which bodies have to deal with the highest number of complaints and what is the profile of the most active requesters.

Common features of FOI laws

Most often, the executive and administrative bodies of the state are concerned by the FOIA.

Various countries, including Ireland, provide a list of all bodies covered. However, provisions provided by other states remain rather elusive. Moreover, countries like the United Kingdom have excluded specific departments of the legislation because they handle sensitive information. According to Banisar (2006), a best practice would be to make all ministries subject to the FOIA, and raise exemptions when those are legitimate; they should be applied in accordance with the current legislation. Common features of FOI laws therefore include the right to access information detained by governments and national administrations, and frequent exemptions related to sensitive information (national interests). We will not address here the issues of appeals and oversight, documents’ accessibility, or the regime of sanctions, as they vary strongly among all countries that have adopted FOI laws. All these aspects have already been briefly discussed by Banisar (2006).

A second common feature refers to the problems faced by administrations when dealing with FOI requests.

As part of a culture of secrecy, most countries still struggle with resisting administrations, and a typology has even been established by Pasquier and Villeneuve (2007). In some countries, the low level of complaints tends to reinforce this phenomenon, and as a result prevents the development of a culture based on openness and transparency. Citizens’ participation is therefore essential but is sometimes undermined by delays and fees demanded by national authorities. More restrictive regulations should be specified in the law in order to avoid such a situation, which reduces incentives to get involved in the process and consequently diminishes the efficiency of the law. Sometimes used as a deliberate strategy, delays are also the result of understaffed offices in certain cases. This is an element that should be improved according to the evolution of the law usage and the new managerial requirements involved (in terms of staff, resources, and budget). Records management and the right of privacy should also be taken into account very seriously.

Who are the requesters?

Once again, the origin of the complaints filed depend on the countries considered. In most countries, though, and where detailed information is available, a majority of requesters are the general public, looking for personal information.

This is especially the case in Ireland, where more than 60% of the requests were personal in 2015, a trend that seems to continue since 2005, when 70% of the complaints were based on personal reasons. However, in 2000 (the first year for which we have data about FOI in Ireland), interest for non-personal information was higher (53%).

In New Zealand, the general public also tops the list of requesters’ types, with 64% of complaints submitted by individuals under the Official Information Act in 2015. The media are a distant second, with only 17.7%. All other categories, including companies, interest groups, and researchers all score below 10%. This tendency is observed for several years in the country. In 2000, individuals already formed the leading group, with around 46%. Members of the Parliament and political party research units followed with 19.5%, and the media were third with around 13%.

In Canada, the public tops the list in 2015 with 41%, ahead of the private sector (businesses) with 37% and the media (11.5%). Complaints have generally emanated more from companies than the citizens since 2000. The media have always been a significant source of requests, but well behind businesses and the public (11.5% in 2015 / 9% in 2006 and 10.6% in 1997). In Switzerland, data are available for requests submitted to the Commissioner for mediation processes. The media have ranked first since 2009 (except for 2013), after two first years of application of the law. As in other cases, individuals are also among the top 3, together with specific interest groups most of the time. Unfortunately, detailed data for other states have not been published so far. Table 3 shows the evolution of requests submitted by citizens since 2007 in 4 countries. This particular group has been selected here because they top the list in three countries and are a close second in Switzerland in 2015.

Table 3. Evolution of requests submitted by citizens compared to other groups, 2007-2015 (in %)

| Ireland | Canada | New Zealand | Switzerland* | |

| 2007 | 60 | 32.4 | 37.8 | 33.3 |

| 2008 | 57 | 34.2 | 39.2 | 23.1 |

| 2009 | 59 | 34.2 | 44.9 | 19.5 |

| 2010 | 60 | 35.2 | 48.7 | 15.6 |

| 2011 | 66 | 37.6 | 54.1 | 15.4 |

| 2012 | N/A | 39.1 | 65.1 | 26.9 |

| 2013 | 73 | 40.4 | 76.6 | 35.5 |

| 2014 | 68 | 39.5 | 55.4 | 21.1 |

| 2015 | 56 | 41.2 | 63.9 | 23.5 |

*In cases where the Information Commissioner is involved

Figures seem to show a significant interest from the public for administrative documents.

However, most requests emanating from “clients of public bodies” are targeting personal information in Ireland, explaining the particularly high figures described in table 3. In New Zealand, there is also a large interest from the general public, at least higher than Canada, where businesses make a more extensive usage of the law. In Switzerland, it remains difficult to conduct a precise analysis of the requesters’ types, because statistics focus on the mediation processes, which concern only 20% of the volume of complaints submitted to all departments.

All in all, the different systems and methods of counting make any comparative study very difficult. The only general conclusion that could be drawn here refers to the global “good” performance of the general public in terms of complaints submitted compared to other types of requesters. In this sense, there is no exclusive usage of the law by specific interest groups, lawyers or companies. At the same time, there could be more participation, because citizens’ involvement adds to the legitimacy of the law and the perception of a more open government.

To what public bodies are most FOI requests submitted to?

With respect to FOI, countries usually maintain a record of their national departments. Institutions are most of the time ranked according to the number of requests received, which allow for a more accurate comparative analysis (avoiding the different methods of counting). This section does not take into account the type of requesters, mainly because no such detailed data are available in many countries.

In Canada, citizenship and immigration has received 50% of all requests sent to national authorities in 2015, well above Canada Border Services Agency (9.8%) and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (4.9%). One can easily see how security preoccupations have prevailed in FOI requests that year. Historically, Citizenship and immigration has always been the institution that has gathered the largest amount of complaints since 2000, above 25% and up to 50% in 2015.

The same analysis applies to Australia, where the Department of Immigration and Border Protection ranks first in the list of agencies by number of FOI requests received. In 2015, more than half of all complaints had been sent to that agency, and only 12.7% to the Department of Human Services. All other bodies have received less than 10% of the total amount (35,550). Historically, the Department of Immigration has topped the list since 2006. The Department of Human Services and the one of Veterans’ Affairs have also continually ranked in the top 5 because of personal requests sent to these agencies. However, a closer look at the statistics shows that in terms of non-personal complaints, the Australian taxation office has been ranking first in the last few years.

More detailed data would be needed to confirm this trend in the next decades.

Finance is also a core concern in Ireland. The Department of Finance is the most targeted body in 2015 with regard to non-personal complaints. The Department of Environment, Community and Local Government, and the Department of Health have also been receiving many requests since 2000, although some of them have been reorganized and renamed. However, in the first years following the enactment of the FOIA, the body that collected the largest amount of complaints was the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform (now the Department of Justice and Equality).

In other countries, concerns switch to other domains.

For instance, the Swiss Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications has received more complaints than any other body since the enforcement of the Transparency law (LTrans) in 2006, only surpassed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2015. The Federal Department of Home Affairs has been receiving an increasing volume of requests recently. This is also the case in the United Kingdom, where a significant amount of complaints has been sent to the Home Office in 2015 (7.1%), just behind the Ministry of Defense (8.1%), the Ministry of Justice (8.5%), and the Department for Work and Pensions (10.2%).

As it is the case in Ireland, health also attracts lots of attention in the UK. Indeed, Health and Safety Executive even tops the list of all Departments of State and other monitored bodies in 2015 (10.4%). The situation was almost the same in 2010, with an even higher volume of requests submitted to the Health and Safety Executive (14.6%).

In conclusion, the main public bodies that deal with FOI requests highly depend on national patterns, based on regional and national issues. It seems however that in large immigration countries like Australia and Canada, there is a focus on security and border issues. More generally, the Departments of Home Affairs and Finance are bodies that typically receive a significant amount of complaints in most countries, while particularities result from differences between states selected in this study (e.g. environment, transport, energy and communications in Switzerland, or justice and equality in Ireland).

The evolution of FOI requests: case studies

As mentioned above, the evolution of the number of FOI requests sent to national governments over the past few years is dependent on different methods of counting, and a deep analysis would involve the same levels of details in published reports from the responsible bodies, which is not the case in all countries. For instance, who are the requesters? What type of requester sent what kind of complaint to what body? Surveys would also be needed to highlight the motivation behind the requests. Moreover, the variety of the political systems, and the various dimensions of the FOIA – which differ in almost every country – does not allow for a systematic study.

As a consequence, there is a need to focus on case studies with respect to the volume of FOI requests submitted since the enforcement of the law in all states selected in this paper. Data will be provided for all cases in absolute numbers. In the end, theoretical hypotheses will be presented, and they constitute as many paths for future research in the field.

Filed under: Latest Features