By Greg Michener

2008 was a big year for freedom of information movements in Latin America. Three countries passed access to information laws last year (Uruguay, Chile, and Guatemala), officially institutionalizing the publics right to know. Varying degrees of media attention, however, had a significant effect on the relative strength of each law. I have found a strong correlation between media output on the issue of transparency and the strength of corresponding laws in these countries and others. This analysis is especially relevant for Brazil, the next Latin American country poised to pass a law. A bill is now before the Chamber of Deputies that will likely pass in the coming weeks. However, the prospects for strong legislation appear to be dim, if we apply this measuring stick to Brazils media agenda and look at the overall news coverage of the law.

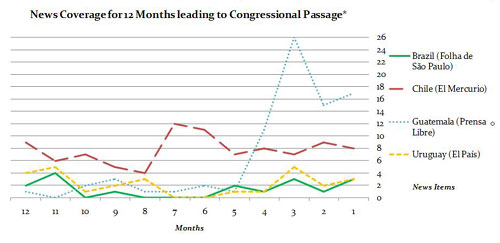

The 2008 laws passed by Chile, Guatemala, and Uruguay reflect varying levels of support for right-to-know laws. Uruguays right-to-know movement was led by a group referred to as the Grupo Archivos y Acceso a la Informacin Pblica (GAIP), comprised of archivists, human rights, and anticorruption advocates, as well as professional legal and media associations. GAIP elaborated two bills, an archives law and an access to public information measure in 2005, presenting them to Congress and the government in early 2006. For the 12 months prior to congressional enactment of the Access to Public Information bill (18381) in October 2008, Uruguays leading daily, El Pas, produced an average of 2.3 news items per month on access to information as a right or legal measure. [1] Only 1.1 of these articles each month contained more than a passing reference. Edison Lanza, one of GAIPs leaders and a prominent member of the Uruguayan Press Association, admitted that media owners never opposed it, but they never undertook a campaign in favor of it. [2]

Chile and Guatemala tell different stories. For the 12 months prior to congressional passage in January 2008, Chiles leading daily, El Mercurio, produced over three times more coverage than Uruguays El Pas, with an average stream of 7.8 news items per month. More than half of those news items focused directly on the topic. Led by an able NGO dedicated to access rights, Proacceso, Chiles right-to-know movement secured political support for the law after an important Inter-American Court ruling [3] and several high-profile corruption scandals. The mainstream media were overly reserved during most of Chiles decade-long right-to-know campaign. But according to Pablo Olmedo, co-founder of Proaccesso and now President of Chiles Council for Transparency, they were there when it counted most.

In Guatemala, media support for an access to information law surged when news broke that leaders of the National Assembly put more than US$11 million of public money at their discretion. The scandal revealed systemic misuse and theft of public funds in Congress. Closely affiliated with the Inter-American Press Association, Guatemalas leading newspaper, Prensa Libre, averaged 6.3 news items per month on access to information. Most items were penned during the four months prior to the laws passage, which accounts for why five out of six news items focused squarely on the issue of information rights. Other Guatemalan media outlets, such as El Peridico, also set strong agendas for the right-to-know.

The respective strength of media campaigns in the three countries compare favorably with the face-value strengths of laws enacted. On an original 40-question evaluation using criteria from best practice laws and assessments, Uruguays law emerged as moderately weak with a score of 1.7 out of a possible 3. In contrast, Chile and Guatemalas laws each earned moderately strong scores of 2.3. [4] Some of the questions include:

- Who can request information and is a justification needed for making a request (principle of non-discrimination)?

- What is the relative power of the oversight body? For example, are its decisions considered binding or are they mere recommendations? Does it have the power to investigate and sanction?

- To what degree is there an obligation to publish information about public bodies? [5]

Uruguays law exhibits several notable deficiencies. Information rights expert Toby Mendel of Article 19 [6] asserts that the omission of a definition for public bodies in the Uruguayan measure is very problematical. It virtually serves as a carte blanche for government to exempt institutions from disclosure. Uruguays law also lacks any internal or external means of resolving appeals when information is denied; instead it defers to the courts. Moreover, the appointees to the oversight body are not vetted by Congress and report to the executive branch instead of parliament. This falls outside of international standards, in which council members are typically appointed by the President and confirmed by a two-thirds congressional majority. Uruguays right-to-know movement, GAIP, did include such definitions in their draft law, but government thought the better. Negotiation was difficult; the Presidents party enjoyed majorities in Congress, and there was little media coverage to make much of advocate demands.

In contrast, much media coverage was devoted to Chiles proposed Transparency Council, which undoubtedly helped defeat political resistance to its creation. Among other powers, it is charged with hearing appeals and complaints. And although Guatemalas law only furnishes an internal appeal mechanism, it is a better first option than appealing directly to the court system, which tends to be expensive and time consuming.

Brazil could be the next Latin American right-to-know success. But success may elude Brazil if the news medias relative silence persists. Brazils leading progressive newspaper, Folha de Sao Paulo, produced a mere 1.4 news items per month on access to information rights during the year May 1, 2008, to May 1, 2009. Journalists themselves view support to be weak. In a May 2008 survey I conducted at a conference on Brazilian journalism [7], 182 journalists gave the Brazilian press a 6 out of 10 for the degree to which the Brazilian media supports an access to information law. Fortunately, when journalists were asked the degree to which they believed an access to information law was necessary, the average response was 8 out of 10.

So far, the limited reach of the Brazilian campaign for the right-to-know has permitted the government to delay and resist, and a draft of the proposed law has received criticism from Brazilian and international FOI experts. During a recent seminar in Brasilia, officials from Mexicos IFAI and Chiles Transparency Council pointed to the lack of an independent agency to implement and oversee the law. Also during the same conference, it became clear that one of the keynote government speakers, the President of the National Congress, Deputado Michel Temer, did not know exactly what was being advocated. Because the conference was sponsored by a media association (Association for Brazilian Investigative Reporters / ABRAJI), he erroneously interpreted the event as advocating media rights to information. He went on to claim that secrecy was a necessary means of ensuring the tranquility of the country, to the mutual embarrassment of all present.

History is full of examples of how media have played key roles in bringing about strong laws. Clearly, if the media do not dedicate more coverage to the issue, politicians can hardly be expected to get it right, let alone other sectors of society. News media professionals are traditionally viewed as caretakers of democracy, which includes the responsibility of covering reforms that can improve the quality of government and citizens rights, if not their own rights. Failure to do so casts doubt on one of the most basic foundations of a functional democracy: an independent and civic-minded press.

Greg Michener is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. He plans on defending this fall 2009. For more information, please contact Greg at gregmichener@mail.utexas.edu.

NOTES

[1] Collection of news items is based on archival analysis of all reporting, including articles, editorials, or interviews, and were counted as news items only if they included the words acceso a la informacin or acceso a informacin and made explicit or implicit reference to access to information as a right or to an access to information law. These terms were chosen for their ubiquitous use. For example, all Hispanic American laws include these words in their titles.

[2] Personal interview, March 2009.

[3] Claude Reyes and Others v. Chile (12.108).

[4] Behind Mexico, which scored a strong 2.7, Chile and Guatemalas laws have the regions most promising laws based on their face-value legal soundness.

[5] The evaluation was designed by the author and is currently still in draft form and a work in progress. However, please contact me if you would like to see the current version. Article 19s model law, assessments, and affiliated experts were employed as first-order sources of best practice criteria in the design of the evaluation.

[6] The author gratefully acknowledges Toby Mendel, Senior Legal Council at Article 19, London, for a draft copy of his upcoming book on Latin American right-to-know laws.

[7] Association for Brazilian Investigative Reporters (ABRAJI), Belo Horizonte, May 2008.

Filed under: Latest Features